-

- Art. 3 FC

- Art. 5a FC

- Art. 6 FC

- Art. 10 FC

- Art. 13 FC

- Art. 16 FC

- Art. 17 FC

- Art. 20 FC

- Art. 22 FC

- Art. 26 FC

- Art. 29a FC

- Art. 30 FC

- Art. 31 FC

- Art. 32 FC

- Art. 42 FC

- Art. 43 FC

- Art. 43a FC

- Art. 45 FC

- Art. 55 FC

- Art. 56 FC

- Art. 60 FC

- Art. 68 FC

- Art. 74 FC

- Art. 75b FC

- Art. 77 FC

- Art. 81 FC

- Art. 96 para. 1 FC

- Art. 96 para. 2 lit. a FC

- Art. 110 FC

- Art. 117a FC

- Art. 118 FC

- Art. 123a FC

- Art. 123b FC

- Art. 130 FC

- Art. 136 FC

- Art. 164 FC

- Art. 166 FC

- Art. 170 FC

- Art. 178 FC

- Art. 189 FC

- Art. 191 FC

-

- Art. 11 CO

- Art. 12 CO

- Art. 50 CO

- Art. 51 CO

- Art. 84 CO

- Art. 97 CO

- Art. 98 CO

- Art. 99 CO

- Art. 100 CO

- Art. 143 CO

- Art. 144 CO

- Art. 145 CO

- Art. 146 CO

- Art. 147 CO

- Art. 148 CO

- Art. 149 CO

- Art. 150 CO

- Art. 633 CO

- Art. 701 CO

- Art. 715 CO

- Art. 715a CO

- Art. 734f CO

- Art. 785 CO

- Art. 786 CO

- Art. 787 CO

- Art. 788 CO

- Art. 808c CO

- Transitional provisions to the revision of the Stock Corporation Act of June 19, 2020

-

- Art. 2 PRA

- Art. 3 PRA

- Art. 4 PRA

- Art. 6 PRA

- Art. 10 PRA

- Art. 10a PRA

- Art. 11 PRA

- Art. 12 PRA

- Art. 13 PRA

- Art. 14 PRA

- Art. 15 PRA

- Art. 16 PRA

- Art. 17 PRA

- Art. 19 PRA

- Art. 20 PRA

- Art. 21 PRA

- Art. 22 PRA

- Art. 23 PRA

- Art. 24 PRA

- Art. 25 PRA

- Art. 26 PRA

- Art. 27 PRA

- Art. 29 PRA

- Art. 30 PRA

- Art. 31 PRA

- Art. 32 PRA

- Art. 32a PRA

- Art. 33 PRA

- Art. 34 PRA

- Art. 35 PRA

- Art. 36 PRA

- Art. 37 PRA

- Art. 38 PRA

- Art. 39 PRA

- Art. 40 PRA

- Art. 41 PRA

- Art. 42 PRA

- Art. 43 PRA

- Art. 44 PRA

- Art. 45 PRA

- Art. 46 PRA

- Art. 47 PRA

- Art. 48 PRA

- Art. 49 PRA

- Art. 50 PRA

- Art. 51 PRA

- Art. 52 PRA

- Art. 53 PRA

- Art. 54 PRA

- Art. 55 PRA

- Art. 56 PRA

- Art. 57 PRA

- Art. 58 PRA

- Art. 59a PRA

- Art. 59b PRA

- Art. 59c PRA

- Art. 60 PRA

- Art. 60a PRA

- Art. 62 PRA

- Art. 63 PRA

- Art. 64 PRA

- Art. 67 PRA

- Art. 67a PRA

- Art. 67b PRA

- Art. 73 PRA

- Art. 73a PRA

- Art. 75 PRA

- Art. 75a PRA

- Art. 76 PRA

- Art. 76a PRA

- Art. 90 PRA

-

- Art. 1 IMAC

- Art. 1a IMAC

- Art. 3 para. 1 and 2 IMAC

- Art. 8 IMAC

- Art. 8a IMAC

- Art. 11b IMAC

- Art. 16 IMAC

- Art. 17 IMAC

- Art. 17a IMAC

- Art. 32 IMAC

- Art. 35 IMAC

- Art. 47 IMAC

- Art. 55a IMAC

- Art. 63 IMAC

- Art. 67 IMAC

- Art. 67a IMAC

- Art. 74 IMAC

- Art. 74a IMAC

- Art. 80 IMAC

- Art. 80a IMAC

- Art. 80b IMAC

- Art. 80c IMAC

- Art. 80d IMAC

- Art. 80h IMAC

-

- Vorb. zu Art. 1 FADP

- Art. 1 FADP

- Art. 2 FADP

- Art. 3 FADP

- Art. 4 FADP

- Art. 5 lit. c FADP

- Art. 5 lit. d FADP

- Art. 5 lit. f und g FADP

- Art. 6 para. 3-5 FADP

- Art. 6 Abs. 6 and 7 FADP

- Art. 7 FADP

- Art. 10 FADP

- Art. 11 FADP

- Art. 12 FADP

- Art. 14 FADP

- Art. 15 FADP

- Art. 18 FADP

- Art. 19 FADP

- Art. 20 FADP

- Art. 22 FADP

- Art. 23 FADP

- Art. 25 FADP

- Art. 26 FADP

- Art. 27 FADP

- Art. 31 para. 2 lit. e FADP

- Art. 33 FADP

- Art. 34 FADP

- Art. 35 FADP

- Art. 38 FADP

- Art. 39 FADP

- Art. 40 FADP

- Art. 41 FADP

- Art. 42 FADP

- Art. 43 FADP

- Art. 44 FADP

- Art. 44a FADP

- Art. 45 FADP

- Art. 46 FADP

- Art. 47 FADP

- Art. 47a FADP

- Art. 48 FADP

- Art. 49 FADP

- Art. 50 FADP

- Art. 51 FADP

- Art. 52 FADP

- Art. 54 FADP

- Art. 55 FADP

- Art. 57 FADP

- Art. 58 FADP

- Art. 60 FADP

- Art. 61 FADP

- Art. 62 FADP

- Art. 63 FADP

- Art. 64 FADP

- Art. 65 FADP

- Art. 66 FADP

- Art. 67 FADP

- Art. 69 FADP

- Art. 72 FADP

- Art. 72a FADP

-

- Art. 2 CCC (Convention on Cybercrime)

- Art. 3 CCC (Convention on Cybercrime)

- Art. 4 CCC (Convention on Cybercrime)

- Art. 5 CCC (Convention on Cybercrime)

- Art. 6 CCC (Convention on Cybercrime)

- Art. 7 CCC (Convention on Cybercrime)

- Art. 8 CCC (Convention on Cybercrime)

- Art. 9 CCC (Convention on Cybercrime)

- Art. 11 CCC (Convention on Cybercrime)

- Art. 12 CCC (Convention on Cybercrime)

- Art. 16 CCC (Convention on Cybercrime)

- Art. 18 CCC (Convention on Cybercrime)

- Art. 25 CCC (Convention on Cybercrime)

- Art. 27 CCC (Convention on Cybercrime)

- Art. 28 CCC (Convention on Cybercrime)

- Art. 29 CCC (Convention on Cybercrime)

- Art. 32 CCC (Convention on Cybercrime)

- Art. 33 CCC (Convention on Cybercrime)

- Art. 34 CCC (Convention on Cybercrime)

-

- Art. 2 para. 1 AMLA

- Art. 2a para. 1-2 and 4-5 AMLA

- Art. 2 para. 2 AMLA

- Art. 2 para. 3 AMLA

- Art. 3 AMLA

- Art. 7 AMLA

- Art. 7a AMLA

- Art. 8 AMLA

- Art. 8a AMLA

- Art. 11 AMLA

- Art. 14 AMLA

- Art. 15 AMLA

- Art. 20 AMLA

- Art. 23 AMLA

- Art. 24 AMLA

- Art. 24a AMLA

- Art. 25 AMLA

- Art. 26 AMLA

- Art. 26a AMLA

- Art. 27 AMLA

- Art. 28 AMLA

- Art. 29 AMLA

- Art. 29a AMLA

- Art. 29b AMLA

- Art. 30 AMLA

- Art. 31 AMLA

- Art. 31a AMLA

- Art. 32 AMLA

- Art. 38 AMLA

FEDERAL CONSTITUTION

MEDICAL DEVICES ORDINANCE

CODE OF OBLIGATIONS

FEDERAL LAW ON PRIVATE INTERNATIONAL LAW

LUGANO CONVENTION

CODE OF CRIMINAL PROCEDURE

CIVIL PROCEDURE CODE

FEDERAL ACT ON POLITICAL RIGHTS

CIVIL CODE

FEDERAL ACT ON CARTELS AND OTHER RESTRAINTS OF COMPETITION

FEDERAL ACT ON INTERNATIONAL MUTUAL ASSISTANCE IN CRIMINAL MATTERS

DEBT ENFORCEMENT AND BANKRUPTCY ACT

FEDERAL ACT ON DATA PROTECTION

CRIMINAL CODE

CYBERCRIME CONVENTION

COMMERCIAL REGISTER ORDINANCE

FEDERAL ACT ON COMBATING MONEY LAUNDERING AND TERRORIST FINANCING

FREEDOM OF INFORMATION ACT

FEDERAL ACT ON THE INTERNATIONAL TRANSFER OF CULTURAL PROPERTY

- I. Basis

- II. Scope

- III. Exceptions

- IV. List of criminal offenses (Art. 2 para. 3 lit. a–g AMLA)

- V. General clause

- VI. Professionalism

- VII. Consequences of the obligation to comply

- Bibliography

- Materials

I. Basis

A. Purpose and relationship between paragraphs 2 and 3

1 According to Art. 2 para. 1 AMLA, the Anti-Money Laundering Act applies primarily (lit. a) to financial intermediaries and secondarily (lit. b) to natural and legal persons who trade in goods on a commercial basis and accept cash in the process (dealers). The term “financial intermediaries” encompasses all natural and legal persons described in paragraphs 2 and 3 of the Act.

2 The list in Art. 2 para. 2 AMLA initially refers exclusively to institutions that are directly or indirectly supervised by FINMA as financial intermediaries, whereby reference is made to the respective special laws for their definition.

3 However, since institutions without FINMA authorization can also engage in financial intermediation activities that are (also) “particularly susceptible to money laundering” but “where the risk of abuse for money laundering purposes is less obvious,” the so-called parabanking sector has been made subject to money laundering legislation under the supervision of self-regulatory organizations approved by FINMA in accordance with Art. 24 para. 1 AMLA. The activities covered correspond to the scope of Art. 305ter para. 1 of the Swiss CC. In addition to the general clause, Art. 2 para. 3 lit. a–g AMLA lists a catalog of criminal offenses. While Art. 2 para. 2 AMLA thus refers to the respective license category, Art. 2 para. 3 AMLA refers specifically to the activities covered. How these activities are classified under contract law is not decisive.

4 Para. 3 is a subsidiary final provision in relation to para. 2. This means that the same financial intermediary cannot be subject to both para. 2 and para. 3 at the same time and that para. 3 can only apply if a financial intermediary is not already subject to para. 2 of the AMLA.

B. Regulatory cascade

5 Based on Art. 41 para. 1 AMLA, the Federal Council specifies the scope of application of Art. 2 para. 3 AMLA in Art. 2 ff. of the Ordinance on Combating Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing (Money Laundering Ordinance, AMLO) of November 11, 2015.

6 In its Circular 2011/1 “Activities as a financial intermediary under the AMLO – Explanatory notes on the Anti-Money Laundering Ordinance (AMLO)”, FINMA set out its practice for interpreting money laundering legislation, including examples of activities that are subject to the Anti-Money Laundering Act. The FINMA circular has no independent regulatory effect, but is very relevant in practice as a guideline.

7 FINMA Circular 2011/1 replaces the subordinate commentary of the former Money Laundering Control Authority dated October 29, 2008 (UK Kst. AMLA), which continues to serve as an interpretative aid in doctrine and practice due to its more detailed explanations.

C. Structure of the provision

8 Art. 2 para. 3 AMLA contains a general clause with an abstract definition. According to this, persons who “accept or hold assets of third parties on a commercial basis or participate in their investment or transfer” are initially considered financial intermediaries.

9 The paragraph then contains a specific list of catalogued circumstances, which is not exhaustive according to the connecting term “in particular.” Here, too, the catalogued circumstances take precedence over the general clause in the sense of a lex specialis. It must therefore first be examined whether a circumstance under Art. 2 para. 3 lit. a–g AMLA exists. If this is not the case, the second step is to examine whether the general clause could be fulfilled. One argument in favor of this approach is that some of the catalog cases impose special requirements on professional conduct.

10 Both the law and the ordinance contain exemptions that must be observed. Art. 2 para. 4 AMLA excludes certain activities and institutions from the scope of the AMLA. Art. 2 para. 2 AMLO contains specific exemptions that refer to Art. 2 para. 3 AMLA. These exceptions apply to both the general clause and the special circumstances.

11 The exemplary list of activities in Art. 2 para. 3 AMLA should not obscure the fact that some of the cases listed in the catalog go beyond the scope of the general clause. Accordingly, not every person who meets the criteria of a case listed in the catalog necessarily also meets those of the general clause. Rather, the catalog contains separate special circumstances that extend the scope of application of Art. 2 para. 3 AMLA and have an independent meaning. From a legal perspective and for better understanding, it would be desirable to indicate this accordingly in the wording of the law.

D. Interpretation of the provision

12 The interpretation of the AMLA by the AMLA supervisory authority was based on the purpose of the AMLA (Art. 1) with corresponding materials in a form that deliberately aimed to apply the AMLA only to persons active in the financial sector. Accordingly, only activities attributable to the financial sector, including those listed in the catalog in Art. 2 para. 3 lit. a–g AMLA, should be subject to Art. 2 para. 3 AMLA. This catalog should form the “starting point for the interpretation of the general clause.” Activities that are comparable or very similar to those listed in the catalog should be examined on a case-by-case basis and, if necessary, be subject to the AMLA via the general clause. Other activities such as real estate, antiques, or art trading are expressly excluded. These findings remain valid even though the scope has been extended to include trading since 2016 and, according to the ongoing revision of the law, will also include consulting services outside of financial intermediation in the future. Art. 2 para. 3 AMLA remains reserved even with the latest revision of financial intermediation and is clearly distinguished from other services.

13 The general clause of Art. 2 para. 3 AMLA is formulated in abstract and open terms in order to subject activities that are attractive for money laundering and are neutral in terms of technology and innovation to the due diligence and reporting obligations of the AMLA. New forms of financial intermediation should not have to be regulated retrospectively. According to the case law of the Federal Supreme Court, the interpretation of subordination must therefore be handled restrictively. The “regulatory technique used, which merely describes the group of financial intermediaries in an open and exemplary manner, requires that, in addition to the wording, the meaning and purpose of the norm be taken into account more strongly in its interpretation.” In legal doctrine, this consideration is interpreted to mean that the application of money laundering regulations is only justified in cases where there are activities and circumstances that pose a money laundering risk. However, if such a risk is only low, the scope of the due diligence obligations should also be adjusted accordingly. This approach is reflected in particular in the simplified due diligence obligations under the GwV-FINMA.

14 The Federal Administrative Court has clarified that it is not the intention of the AMLA or the AMLO to require proof or justification of a specific money laundering risk in addition to the legally defined elements of the offense in order to be subject to the law. If an activity meets the legal criteria, it is justified that it is subject to the law without further proof of risk. This is appropriate because the legislator has only included circumstances with an inherent money laundering risk in the law, which is why a further risk assessment by the authorities applying the law is not necessary.

E. Recommended assessment method

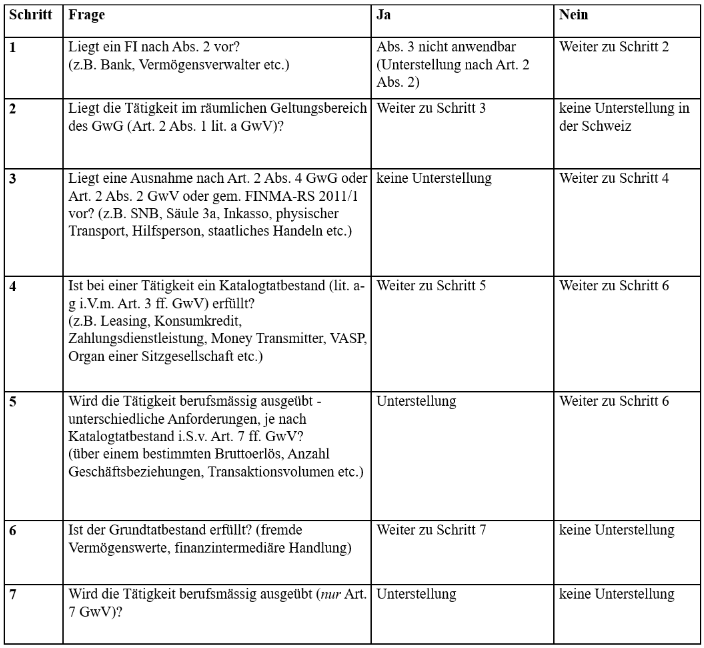

15 The following assessment scheme can be used to determine whether an activity is subject to the AMLA:

II. Scope

A. Geographical

16 In contrast to financial intermediaries under Art. 2 para. 2 AMLA, the geographical scope of financial intermediaries under Art. 2 para. 3 AMLA is expressly regulated in the Anti-Money Laundering Ordinance (AMLO). According to Art. 2 para. 1 lit. a AMLO, the AMLA applies to financial intermediaries who actually operate in Switzerland or from Switzerland.

17 According to FINMA practice, a financial intermediary operates in Switzerland or from Switzerland if it has its registered office in Switzerland or is entered in the commercial register (formal establishment) or if it employs persons in Switzerland who permanently carry out or conclude financial intermediation activities for it in Switzerland or from Switzerland or who can legally oblige it to do so (de facto branch). The geographical scope of the AMLA is therefore determined by the place where the financial intermediation activity is predominantly carried out.

18 In the case of a formal establishment or branch office, the geographical reference point is the place of residence (for natural persons/sole proprietorships) or the registered office (for legal entities) as the formal center of activity. A company with its registered office in Switzerland is therefore subject to the AMLA, even if it only has a C/O address here and both its actual management and the focus of its operational financial intermediation activities are located abroad.

19 Persons who permanently support the foreign financial intermediary in carrying out significant parts of its financial intermediation activities in Switzerland or from Switzerland fall under the category of de facto branches, but not those constellations in which only the customer has a connection to Switzerland. Accordingly, branches of companies that are incorporated under foreign law and have their headquarters abroad, but whose financial intermediation activities are mainly carried out from Switzerland, are subject to regulation. An activity is carried out from Switzerland if, for example, the contractual relationship with the client is managed by the financial intermediary in Switzerland, even if the transactions are executed by the branch abroad.

20 According to FINMA practice, subordination under the AMLA requires a certain degree of permanence of the activity in Switzerland, while purely temporary activities are not considered permanent. The element of permanence is not defined in more detail in FINMA Circular 2011/1 and requires a case-by-case assessment. The criteria used in doctrine are the absolute duration of the activity, the regularity of presence, the type of financial intermediary activity, and the mechanism for exercising physical presence.

21 The personal connection implies a distinction from a purely mechanical connection. A server or purely online services in Switzerland therefore do not constitute an activity relevant to the AMLA. As long as a financial intermediary in Switzerland has staff who merely acquire customers and maintain customer relationships, but in no way commits the financial intermediary, i.e., does not conclude contracts on behalf of the represented party and does not carry out financial intermediation transactions or essential components of such transactions, there is no physical presence in Switzerland within the meaning of Art. 2 para. 1 lit. a AMLO. Purely administrative or technical support therefore does not fall within the scope of the AMLA.

22 In the case of financial intermediaries domiciled or headquartered abroad, as with financial intermediaries headquartered in Switzerland, it must be examined on a case-by-case basis whether their activities in Switzerland meet the requirements for professional activity as a financial intermediary in accordance with Art. 7 AMLO. If this is the case, they are subject to the AMLA. The decisive factor for subordination is the activity actually carried out in Switzerland.

B. Personal and factual

23 Anyone who actually carries out the financial intermediary activities defined in Art. 2 para. 3 AMLA is personally subject to the AMLA. A person is only subject to the AMLA in relation to these activities. Accordingly, the due diligence obligations of the AMLA must only be observed in business relationships that are related to financial intermediary activities.

24 It is conceivable that a supervised activity may be carried out by several persons. In such a case, only the joint action of all persons fulfills the criteria of Art. 2 para. 3 AMLA. In such cases, all persons involved are considered financial intermediaries within the meaning of para. 3.

25 The financial intermediary may be a natural or legal person. The following applies to partnerships: If activities relevant to supervision are carried out by a general partnership or a limited partnership, the partnership itself is a financial intermediary. If they are the subject of a simple partnership, each partner individually becomes a financial intermediary. In the latter case, the provisions of the partnership agreement are decisive for practical implementation.

26 The decisive factor for subordination is the exercise of the activity described in Art. 2 para. 3 AMLA and commented on below. Finally, it should be noted that even financial intermediation activities that meet the criteria only fall within the material scope of the AMLA if the requirement of commercial practice set out in Chapter VI is met and none of the exceptions described in Chapter III apply.

III. Exceptions

A. General

27 In the present case, a distinction must be made between exceptions under the law, under the ordinance, and under FINMA practice, whereby these are not (only), as might be expected, uniformly defined in accordance with the regulatory cascade, but represent different types of exceptions.

28 Art. 2 para. 4 AMLA provides for general exceptions to the registration requirement for institutions and activities that are considered financial intermediation but are not subject to registration due to the absence of money laundering risk.

29 Art. 2 para. 2 AMLO lists specific activities within the financial sector that are not classified as financial intermediation. FINMA has clarified these exemptions in a circular (see III.B. below).

30 Art. 2 para. 2 lit. b AMLO also provides for exceptions for auxiliary persons who carry out financial intermediation activities but are already covered by the client and therefore do not require separate supervision (see III.C. below).

31 In addition, in its practice, FINMA provides for financial intermediation activities in the form of (state) sovereign activities as a further exception to the obligation to comply (see III.D. below).

32 With regard to the list of criminal offenses in Art. 2 para. 3 lit. a–g AMLA, further information that could be described as “exceptions” can be found in Art. 3 ff. AMLO. For example, Art. 3 AMLO lists a catalog of credit relationships that are not to be understood as credit transactions within the meaning of the AMLA. In the present case, such exceptions are examined in the context of the positive elements of the offense (see Chapter IV.B.7.). The absence of a professional activity could also be considered an “exception” (Art. 7 ff. AMLO). In the present case, however, this is also understood as a positive criterion and is therefore examined separately in Chapter VI. The same applies to the “exception” already outlined above, namely the absence of a connection to the geographical scope of Switzerland in accordance with Art. 2 para. 1 lit. a AMLA (see Chapter II.F.). The absence of a connection to the financial sector is also not considered an exception, but must be examined as a positive prerequisite in the general clause (see Chapter V.C.).

B. Non-regulated financial intermediaries

33 According to Art. 2 para. 2 and para. 3 AMLA, institutions whose activities are unlikely to be abused for money laundering would also be subject to the AMLA. The law provides for general exceptions to the obligation to comply in Art. 2 para. 4 AMLA.

C. No financial intermediation activities

1. Physical transport and storage

34 According to Art. 2 para. 2 lit. a no. 1 AMLO, persons who are engaged in the purely physical transport or purely physical storage of assets are not considered financial intermediaries. This refers to the transport of assets from one place to another and the purely physical storage of assets. The custody of securities is expressly reserved (Art. 6 para. 1 lit. c AMLO).

2. Debt collection

35 Debt collection pursuant to Art. 2 para. 2 lit. a no. 2 AMLO is also not considered financial intermediation. This is the case when a person collects a due claim on behalf of a creditor. The agent acts either as the direct representative of the creditor or in their own name vis-à-vis the debtor after the claims have been transferred to them by the creditor on a fiduciary basis. The decisive factor is that the agent has carried out the transfer on behalf of the creditor, which must be determined on the basis of circumstantial evidence. As a rule, the service is remunerated by the client.

36 Debt collection can also be considered to have taken place if the agent acts within a closed circle of recipients of goods or services. The purpose of the assignment is to ensure the smooth processing and simplification of payments to the supplier of the goods or services.

37 If the agent only has a contractual relationship with the creditor of the claim and acts on their behalf, this is usually a debt collection order, which does not constitute a financial intermediation activity. However, if the assets thus received are not forwarded to the creditor itself but to a third party in accordance with the creditor's instructions, this forwarding in turn constitutes a financial intermediation activity, whereby the party that previously collected the claim then acts as a financial intermediary between the creditor and the third party.

38 All due diligence obligations under the AMLA are linked to a contractual customer relationship. However, the (main) customer of a debt collection agency is always the creditor and never the debtor. If there is no contractual relationship between the debt collection agency and the debtor, the flow of money is considered debt collection, which is not subject to the AMLA. In this sense, debt collection activities on behalf of the creditor are excluded from the scope of the AMLA, as the debtor from whom the assets originate is not usually a contractual partner of the agent and therefore cannot be identified.

39 Thus, a property manager who, in the course of normal property management, receives amounts on behalf of, at the instruction of, and for the account of the property owner is not a financial intermediary within the meaning of the AMLA. If a real estate agent collects the purchase price from the buyer on behalf of the seller and is remunerated by the seller, this is also a collection activity that is not subject to the AMLA.

40 If the operator of a crowdfunding platform collects due support contributions on behalf of borrowers, this does not constitute a collection activity within the meaning of the AMLA. The same applies to a company in the field of e-commerce or the development and sale of software solutions for payments via the Internet, mobile phones, or similar, which additionally collects due receivables on behalf of the creditor and forwards them to the latter. In some cases, telecommunications providers offer, in addition to telecommunications services, the option of purchasing other services and goods and paying for them via mobile phone. However, if the rights and obligations of the contracting parties with regard to the payment of goods and services are regulated, such a contractual relationship differs from a debt collection order, as a contractual regulation of the payment terms is atypical for debt collection activities. The close contractual relationship with the customer with regard to the terms of payment cannot be limited to a pure debt collection activity by the telecommunications company. In addition, the customer can usually decide whether to pay the provider of value-added services in cash, by credit card, by Maestro card, or by postpaid or prepaid. In such cases, the client for the transfer is therefore the debtor of the service and not the creditor. Without collection activities, such offers are therefore considered to be presumed payment services. When purchasing digital content, however, the question arises as to whether this is an ancillary service.

41 In connection with the operation of an internet platform, e.g., for the purchase, sale, rental, or exchange of services and products, goods, everyday items, etc., there may be indications of a collection activity in the above sense if (a) the payment processor only has a contractual relationship with the creditor; (b) in most cases, the payment processor charges the creditor a fee for providing the service; (c) the economic interest in the payment flow lies mainly with the creditor; (d) the relationship between the payment processor and the debtor is limited to the collection of the claim due, with no further rights and obligations existing or these serving only to ensure the debtor's confidence in the proper processing of payments and the smooth functioning of the platform. The following factors argue against debt collection activities (a) The debtor has an e-account on the payment processor's internet platform, to which they can add credit at will and from which the amount owed is debited when a service is used, or (b) payment via the payment processing system in question is only one of several payment options, and the debtor themselves becomes the principal when they choose a particular payment method. Since such platforms come in many different forms, it is not possible to give a general answer to the question of whether a platform is subject to the AMLA.

3. Ancillary transfer

42 According to Art. 2 para. 2 lit. a no. 3 AMLO, the transfer of assets as an ancillary service to a main contractual service is not subject to the AMLA.

43 According to FINMA practice, four criteria must be cumulatively met in order for a ancillary service to be assumed:

It is essentially an ancillary service that is part of a contractual relationship that is not attributable to the financial sector;

the contracting party providing the main service also provides the ancillary service;

This ancillary service is of secondary importance in relation to the main service, which can generally be assumed if no additional remuneration is charged for the ancillary service apart from the cost-covering expenses.

The ancillary service is closely related to the main service, so that the provision of the main service without the provision of the ancillary financial intermediation service would entail particular difficulties for the contracting parties.

44 FINMA cites as a typical example the case in which a retirement and nursing home, in addition to the contractual main service, pays for goods or services from third parties on behalf of its customers from a deposit previously set up for this purpose. If visitors to a festival can use a chip to top up their festival wristband with credit (up to a certain maximum amount) in order to purchase goods at stands, with the remaining credit being transferred back to the visitors at the end of the event, this may also constitute an ancillary service that is not subject to supervision. The transfer of assets for digital content (e-newspapers, online games, or video-on-demand) by a telecommunications provider may also be an ancillary service. The ancillary service consists of providing billing options to service operators at the expense of the users of the services. In addition, the provision of billing options indirectly supports the distribution of digital content. As a rule, there is a close factual link between the main service and the ancillary service. However, in the case of value-added services based on physical products/goods (purchases), there is no ancillary service. The purchase of physical products/goods has no close factual link with the telecommunications services to be provided. Furthermore, the provision of the main service without the provision of the supplementary financial intermediation service does not pose any particular difficulties for the contracting parties, as the service user can switch to alternative payment options.

45 The execution of payment orders by accountants in addition to accounting services is generally not considered ancillary. Classifying such payment transactions as ancillary services would contradict the spirit and purpose of Art. 4 para. 1 lit. a AMLO and mean that in the case of a power of attorney for a bank account and the execution of fiduciary or bookkeeping accounting, the AMLA would no longer apply. This is precisely not the intention of the legislator.

4. Pillar 3a

46 According to Art. 2 para. 2 lit. a No. 4 AMLO, the operation of pillar 3a pension funds by bank foundations or insurance companies does not constitute financial intermediation. Since the assets in pillar 3a pension funds are generally tied up for the long term and the amount of the payments and their tax exemption are limited by law, this activity is not considered particularly susceptible to money laundering.

47 While insurance policies are reviewed by FINMA and insurance companies are subject to FINMA supervision, bank foundations are subject to the cantonal BVG supervisory authorities. The bank foundation must manage the pension assets at a bank supervised by FINMA (account solution) or through its intermediary (securities account). This exception thus prevents multiple supervision and takes into account the principle of proportionality.

5. Services within the group

48 According to Art. 2 para. 2 lit. a No. 5 AMLA, the provision of services between group companies does not constitute financial intermediation either. In this context, the group is considered an economic unit of companies within the meaning of the AMLA if one company directly or indirectly holds more than half of the votes or capital of the other company or otherwise controls it. A group company that performs cash management or treasury functions within an industrial or commercial enterprise is therefore not a financial intermediary within the meaning of the AMLA. The regulation also applies to structures that are not managed by a legal entity but by a natural person.

49 However, the obligations under money laundering law do not apply to the activities of a supervised financial intermediary which, due to the group exemption within the meaning of Art. 2 para. 2 lit. a No. 5 AMLO, would not in themselves lead to supervision as a financial intermediary under the AMLA. It should also be noted that the issuance of means of payment that can be redeemed by customers at one or more group companies is subject to Art. 2 para. 3 lit. b AMLA.

D. Auxiliary persons

50 According to Art. 2 para. 2 lit. b AMLO, auxiliary persons of financial intermediaries that are licensed in Switzerland or affiliated with a self-regulatory organization (SROs) are considered to be covered by their license/SRO membership if the requirements under no. 1–6 are met. This exception therefore does not depend on the type of activity, but on the fact that the auxiliary persons are already subject to due diligence obligations through their clients. For this exception to apply, the auxiliary persons must:

be carefully selected by the financial intermediary and be subject to its instructions and control (No. 1);

be included in the financial intermediary's organizational measures and receive appropriate training and continuing education (No. 2);

act exclusively on behalf of and for the account of the financial intermediary (No. 3);

be remunerated by the financial intermediary and not by the end customers (No. 4);

in the case of money or value transfer transactions, they must work exclusively for a single licensed financial intermediary or a financial intermediary affiliated with an SRO (“exclusivity clause,” No. 5);

they must have concluded a written agreement with the financial intermediary regarding compliance with the above requirements (No. 6).

51 The financial intermediary that engages the auxiliary person remains responsible under supervisory law for compliance with the due diligence obligations under the AMLA. With the exception of money or value transfers, auxiliary persons may work for several financial intermediaries that are licensed or affiliated with SROs. The latter exception primarily concerns money transfer service providers. In practice, individuals act as auxiliary persons for the responsible financial intermediary in the day-to-day business of money transfer service providers. It is the responsibility of the financial intermediary to ensure that there is an exclusive partnership with the auxiliary persons.

52 One of the prerequisites for the activity of the auxiliary person not to be considered independent financial intermediation is that they act exclusively in the name and on behalf of the financial intermediary (Art. 2 para. 2 lit. b no. 3 AMLO). In contrast, the activity as an organ can only be carried out in its own name. Subsidiaries of financial intermediaries cannot claim the status of an auxiliary person for themselves.

E. State action

53 According to FINMA practice, state action is not subject to the AMLA if it is carried out within the scope of sovereignty, even if the activity itself would be classified as financial intermediation. It must be examined in each individual case whether the activity is carried out within the scope of state sovereignty or not. Indications of a sovereign activity that is not subject to the AMLA include an explicit legal basis, a relationship of subordination, a public task, or the supervisory authority of a higher-level authority.

54 The state is therefore only subject to the AMLA when it acts within the scope of its non-sovereign activities. Since the fulfillment of sovereign tasks can also be transferred to private individuals, it is irrelevant from a money laundering law perspective in what “form” or organizational structure state action takes place and whether the legal relationships in question are to be classified as private law or administrative law contracts. The decisive factor is the criterion of sovereignty, which must be examined on the basis of the criteria described above.

55 According to FINMA practice, debt collection and bankruptcy offices, liquidators, guardians, pension fund administrators, estate administrators, and executors are not financial intermediaries. However, the latter two are subject to the AMLA if they provide financial intermediary services outside the scope of their mandate, for example in connection with their involvement in the distribution of an estate.

IV. List of criminal offenses (Art. 2 para. 3 lit. a–g AMLA)

A. Introduction

56 Despite the use of the term “in particular,” the list of criminal offenses in Art. 2 para. 3 lit. a–g AMLA in some cases goes beyond the general clause in Art. 2 para. 3 and, as the respective lex specialis, takes precedence over it. The list is therefore not exhaustive.

57 Since its introduction, the provision has been revised several times. For example, with effect from January 1, 2006, the Investment Fund Act (IFG) removed the supervisory requirement for investment fund distributors under letter d due to the lack of money laundering risk. The most significant change occurred with the introduction of the FinIA on January 1, 2020, which made asset management subsumed under letter e subject to a licensing requirement and moved asset managers and trustees as financial intermediaries subject to special legislation to Art. 2 para. 2 lit. abis AMLA. This also repealed letter e. However, due to the different thresholds for professional activity in the AMLA and the FinIA, asset managers and trustees who are not subject to the licensing requirement under the FinIA may still fall within the scope of the AMLA via the general clause or via Art. 2 para. 3 letters a–g AMLA letters f or g.

58 Art. 3 ff. AMLO specifies and, in some cases, restricts the list of criminal offenses, whereby it should be noted that Art. 4 AMLO in particular has undergone significant changes in 2021 due to technological developments in the area of payment transactions.

B. Credit business (lit. a)

1. General

59 According to Art. 2 para. 3 lit. a AMLA, persons are considered financial intermediaries if they conduct credit transactions and are not already subject to the special legal supervision of Art. 2 para. 2 AMLA (e.g., as a bank). Examples of this are consumer or mortgage loans, factoring, trade financing, and finance leasing. The provision covers activities that are similar to banking business but do not involve the acceptance of public funds and where refinancing is carried out to a significant extent by the group.

60 Art. 3 AMLO does not specify these activities in a positive sense, but by means of a negative list of activities that are expressly not considered credit transactions. For its part, FINMA specifies the negative list in the GwV-FINMA in its Circular 2011/1 and also sets out its practice for defining cash and consumer loans as well as trade financing, classifying transactions according to their purpose rather than the type of loan.

61 According to prevailing opinion, the term “loan” is interpreted broadly and functionally with reference to international guidelines and materials. In a credit transaction, the lender undertakes to grant the borrower a monetary advantage, and the borrower undertakes to pay interest and repay the debt. This includes all transactions that have such financing as their purpose, are assigned to the financial sector, are carried out professionally, and do not fall under the exceptions. Traditionally, the term “credit” is also understood to mean a loan. In the case of a credit, the lender sets a limit within which the borrower can make withdrawals. In the case of a loan, the lender makes the entire loan amount available to the borrower from the outset, in accordance with the legal definition in Art. 312 of the Swiss Code of Obligations. According to FINMA practice, the term covers any transfer of money to a borrower in return for the borrower's obligation to repay the amount received and pay interest on it.

62 Legal scholars disagree on whether the credit business clarifies or expands the general clause. In any case, the money laundering risk of the credit business is unanimously seen in the assumption of interest and principal payments and is generally considered to be rather low. The specific risk is that assets from predicate offenses will be used to repay loans. There are a number of known cases in which funds from drug trafficking and fraud have been laundered through loans. However, the risk of terrorist financing through the misuse of loans is considered to be significantly greater. Providers of consumer loans are particularly at risk in this regard.

63 No money flows when a settlement is made. Accordingly, there is no possibility of using criminally acquired funds to repay loans. The risk of money laundering, which is why credit transactions are subject to the AMLA, cannot therefore arise in the first place. Although there is a flow of payments, the situation is comparable to unregulated debt collection.

64 The designation and categorization of credit transactions in the law, the ordinance, and the FINMA circular is inconsistent. The following therefore only deals with the types of credit mentioned as examples in the law that need to be discussed in practice.

2. Mortgage loans and other cash loans

65 Mortgage loans (lit. a) are defined as financing transactions for the acquisition and use of real estate or the construction or renovation of buildings, whereby the loan is secured by real estate.

66 According to FINMA practice, mortgage loans – in addition to overdraft facilities, bill discounting, Lombard loans, and long-term loans such as participation loans and subordinated loans – fall under the category of cash loans. It is irrelevant whether the loans are secured by collateral or other means. Pawnshops that grant loans against collateral are subject to the AMLA.

67 Crowdfunding – in particular its subtypes crowdlending and crowdinvesting – also counts as a credit business outside the banking sector and is a generic term for the financing of a project by a large number of investors via an internet platform (with or without consideration). Crowd investing usually refers to the financing of companies in an early stage of development. In return, investors receive shares in the company. Crowd lending focuses on the granting of loans from private individuals to private individuals (with the help of a platform). In return, borrowers pay interest to lenders. Due to the repayment of the loan, crowd lending is susceptible to money laundering.

68 If the platform acts as a lender to the borrower and refinances itself through crowdlending, the platform operator is conducting a lending business that is subject to supervision under Art. 2 para. 3 lit. a AMLA (and may require a special license, e.g., as a bank). A platform that does not act as a lender but allows the lenders' loan amounts to pass through its accounts is not conducting a lending business but may be providing a payment service. If the platform merely offers borrowers the opportunity to find lenders but does not otherwise perform any other functions in the credit relationship between the lenders and the borrower, this is generally not considered a credit business subject to supervision. Even if loans are granted via a platform, each lender remains responsible for checking whether they are subject to the AMLA. On the other hand, the platform operator also has an interest in ensuring that participants comply with regulatory requirements and in obtaining confirmation of this from participants in practice.

3. Consumer loans

69 According to the wording of Art. 2 para. 3 lit. a AMLA, consumer loans are also subject to the AMLA. However, the reference to the KWG in the FINMA circular requires clarification. The definition in the KWG can be used temporarily. However, loans that are exempt from the KWG due to their specific purpose (consumer protection) remain subject to the AMLA. Conversely, the exemptions in the AMLO do not necessarily apply to the KWG.

4. Trade finance

70 The pre-financing of a contracting party in the context of commercial transactions is also considered a loan. According to FINMA Circular 2011/1, the term “trade finance” generally includes discount loans, assignment loans, and finance leases, but also trade credits and sales financing. Trade financing is not subject to the AMLA if it constitutes an ancillary credit grant within the meaning of Art. 3 lit. f AMLO or if the interest and principal payments are not made by the contracting party.

5. (Financial) leasing

71 Finance lease agreements, which are expressly mentioned in Art. 2 para. 3 lit. a AMLA, are subsumed by FINMA under trade financing, but may also constitute a form of consumer credit. Ultimately, this depends on the leased asset (consumer goods or commercial goods) and ultimately makes no difference, as both forms are expressly subject to the AMLA.

72 In finance leases, in addition to the manufacturer, supplier or dealer and the lessee, there is a leasing company that acts as a third party. This company transfers the asset to the lessee for use for a non-cancellable contract term. In return, it receives a fixed lease payment, which is paid directly to the lessor. Ownership of the leased object remains with the lessor. The obligation to comply therefore applies to the lessor as the lender and pre-financier.

6. Factoring

73 In factoring, which is also expressly mentioned in Art. 2 para. 3 lit. a AMLA, the so-called factor can assign a creditor's claims from its business operations in return for payment. The due claim is collected from the debtor. Due to the change of creditor, repayment is not made by the pre-financier, but by a third party (whose debtor). Since, according to FINMA practice, Federal Supreme Court case law, and prevailing opinion, money laundering appears to be effectively ruled out in these activities if the cash flow does not originate from the (pre-financed) contractual partner but from a third party, factoring contra legem (analogous to forfaiting) does not fall under the AMLA. However, there are special types of factoring that do fall under the AMLA, as the repayment of the funds is made by the contractual partner. Factoring may therefore fall under the AMLA if it also fulfills a credit function, i.e., if the factor pays the supplier the amount for the goods before the debtor's payment has been received.

7. Credit agreements not subject to the AMLA

74 In addition to those just mentioned (operating leases, factoring, etc.), Art. 3 AMO excludes further agreements from subjection to the AMLA, although this list is not to be understood as exhaustive (“in particular”).

75 The borrower is not subject to Art. 2 para. 3 lit. a AMLA (Art. 3 lit. a AMLO). Although a money laundering risk on the part of the lender cannot be ruled out with regard to the disbursement of the loan amount, the money laundering risk is traditionally associated with interest and principal payments. As a rule, however, a borrower is not professionally active. The question becomes more relevant in connection with crowdlending, where a borrower faces a large number of lenders. In this case, the money laundering risk on the part of the lenders is likely to be higher than in traditional lending business.

76 According to Art. 3 lit. b AMLA, the granting of loans without interest and fees is not profit-oriented and therefore does not constitute a form of credit similar to banking business. It is therefore not subject to the AMLA, even if pure repayment payments may also pose a money laundering risk. Furthermore, the requirement of professional activity is not met.

77 The granting of loans between a company and its shareholders is also not subject to the AMLO if the respective shareholder holds at least 10 percent of the capital or votes of the company (Art. 3 lit. c AMLO). The basis for this is the capital of the company (share capital including equity capital, share capital). This practice applies to credit relationships with all legal entities in which a capital or voting rights participation is possible.

78 If a lending sister company holds a direct or indirect participation of more than 10 percent in the other sister company, in our opinion the granting of credit is not subject to the AMLA, even if the threshold for professional activity is reached. However, the lending sister company cannot take into account the parent company's participation in the sister company. Without direct or indirect participation between sister companies, the exception in Art. 3 lit. c AMLA does not apply.

79 The granting of loans between employers and employees is also not subject to the AMLA, provided that the employer is obliged to pay social security contributions for the employees involved in the credit relationship. If this condition is not (or no longer) met, the employer becomes a financial intermediary.

80 Credit relationships between affiliated persons within the meaning of Art. 7 para. 5 AMLA are also not subject to the AMLA (Art. 3 lit. e AMLA).

81 The granting of loans that are accessory to another legal transaction is not subject to the AMLA (Art. 3 lit. f AMLO). This is an important distinction in practice. It refers to the granting of a subordinate credit in addition to a main transaction that is not attributable to the financial sector (e.g., purchase of goods, etc.). Examples of this are deferral of payment, granting of a payment deadline, or installment payment agreements. FINMA has developed the following cumulative criteria to determine whether a loan is ancillary:

Provision of a good or service that is not attributable to the financial sector;

The provider of the main service additionally grants a loan to its contractual partner;

The granting of the loan is objectively related to the main service;

The granting of the credit is of secondary importance in relation to the main service; and

The funds used to grant the credit come from the general funds of the provider of the main service.

If the criteria for an ancillary service are met, there is no need to check whether the activity is carried out on a commercial basis within the meaning of Art. 7 ff. AMLO.

82 Operating leases (Art. 3 lit. g AMLA) and, as a rule, direct leases are not subject to the AMLA. In contrast to finance leases, operating leases have a relatively short transfer period for items and/or are easily terminable. The lessor generally bears the costs and risks of the leased item. The situation is comparable to a rental agreement, which is why it does not constitute the granting of credit. The granting of credit in the case of direct leasing, where the manufacturer or dealer is the lessor, is generally considered to be ancillary.

83 Contingent liabilities in favor of third parties, such as sureties or guarantees, are also not considered credit transactions (Art. 3 lit. h AMLA). The contractual partner granting the contingent liability is therefore not subject to the AMLA.

84 Credit intermediation does not constitute an activity subject to supervision. An obligation to comply with the AMLA only arises if, in addition to the intermediation activity, an activity pursuant to Art. 2 para. 3 AMLA is carried out (e.g., receiving and transferring funds on behalf of a customer).

85 Subsidiaries that receive refinancing from the parent company within the group may fall under the group exemption of Art. 2 para. 2 lit. a No. 5 AMLA. For the purposes of the AMLA, a group is considered an economic unit of companies if one company directly or indirectly holds more than half of the votes or capital of the other company or companies or controls them in another way.

86 Venture capital can be invested in a new company by various investors (private individuals, banks, venture capital companies) and in various forms (equity participation, loans). Anyone who participates in the capital of a company is not a lender but an investor and therefore, unlike a lender, not a financial intermediary. In the case of venture capital companies, the difference is even less clear, as they are only allowed to use their funds in the form of equity investments, subordinated loans, or other claims comparable to venture capital. It therefore does not seem justified to consider venture capital companies that grant subordinated loans as financial intermediaries, but not those that invest in capital. It should be noted that risk investments that (may) lead to the loss of criminally obtained funds do not constitute money laundering activities.

C. Payment transaction services (lit. b)

1. General

87 Art. 2 para. 3 lit. b AMLA regulates the special case of “payment transaction services,” which is particularly relevant in practice. The law specifically mentions persons who “make electronic transfers for third parties or issue or manage means of payment such as credit cards and traveler's checks.” The provision was originally introduced for payment transactions developed by the former PTT (Post-, Telefon- und Telegrafenbetriebe; now PostFinance) and for services related to credit cards and traveler's checks and bank checks outside the banking sector. Payment transactions are defined as all payment transactions that transfer means of payment from the sender to the recipient.

88 Art. 4 AMLO also specifies payment services using non-exhaustive abstract definitions. FINMA Circular 2011/1 contains important information on FINMA's practice in this area. Payment service providers generally also comply with the general clause of Art. 2 para. 3 AMLA, as they accept third-party assets and help to transfer them. Technological developments and changes in this area show that the term “by name” is particularly important here and that some of the examples described in the law, ordinance, and FINMA practice are now obsolete (e.g., traveler's checks, etc.).

89 The risk of money laundering in payment transactions is classified as medium to high overall. The inclusion of payment services under the AMLA is justified due to the high liquidity of the assets involved, which are particularly suitable for money laundering due to the possibility of concealing their origin.

90 In the context of artificial intelligence in the financial sector, regardless of the method used, the question arises as to whether the provider in question qualifies as a financial intermediary on the basis of its activities. In this respect, AI-based applications do not pose any particular challenges when assessing whether they are subject to the AMLA.

2. Execution of payment orders / electronic transfers

91 According to Art. 4 para. 1 lit. a AMLO, a payment transaction service in the form of an electronic transfer exists if the financial intermediary transfers liquid financial assets to a third party on behalf of its contracting party and thereby takes physical possession of these assets, has them credited to its own account, or orders the transfer of the assets in the name and on behalf of the contracting party.

92 In addition to the general requirements of the general clause in Art. 2 para. 3 AMLA (financial intermediation, professional activity, activity in the financial sector), subordination under Art. 4 para. 1 lit. a AMLA therefore requires the following criteria to be met:

Power of disposal: The financial intermediary must obtain power of disposal over the assets that do not belong to it.

Liquid financial assets: The term is not defined in Art. 4 para. 1 lit. a AMLO. However, it seems appropriate to understand the term “financial assets” in the same way as the term “assets” within the meaning of the general clause in Art. 2 para. 3. This means that only assets that can be attributed to the financial sector are covered. Financial assets are “liquid” if they can be easily converted into cash or other assets.

Transfer to a third party: According to FINMA practice, all transfers and forwarding of funds carried out on behalf of the debtor are subject to the AMLA. The financial intermediary must have a contractual relationship with both parties to the transfer transaction (so-called tripartite relationship).

93 If this condition is met, subordination applies regardless of whether the debtor compensates the financial intermediary before or after the transfer or forwarding to the third party. This also applies to persons who execute payment orders for third parties by bank proxy, including via e-banking, or if book money payments are forwarded to a beneficiary via a transit account in accordance with the debtor's instructions. Payment orders relating to e-money are also covered by the requirement.

94 Operators of crowdfunding platforms that enable investments in companies are also subject to this requirement if the platform operator itself accepts funds and forwards them to the respective companies.

95 A large proportion of payment orders in Switzerland are processed by banks and the postal service via clearing systems (with foreign countries usually via correspondent banks). While banks are subject to prudential supervision within the meaning of Art. 2 para. 2 lit. a AMLA, the postal service qualifies as a financial intermediary for this area of business in accordance with Art. 2 para. 3 lit. b AMLA. Clearing service providers are not subject to the AMLA if, as is customary in practice, they operate vis-à-vis financial intermediaries within the meaning of Art. 2 para. 2 AMLA (exemption from supervision pursuant to Art. 2 para. 4 lit. d AMLA).

96 The execution of salary payments on behalf of third parties is generally an activity subject to the AMLA, unless the salary payments are made on an ancillary basis and by means of a limited power of attorney by the person who also manages the payroll accounting.

97 Transfers are also not subject to the AMLA if the financial intermediary only has a contractual relationship with the creditor and acts on their behalf, and the assets are not forwarded after collection (collection exception).

3. Assistance with the transfer of virtual currencies

98 According to Art. 4 para. 1 lit. b AMLO, a payment service is also provided if the financial intermediary assists in transferring virtual currencies to a third party, provided that it has an ongoing business relationship with the contracting party or exercises power of disposal over virtual currencies on behalf of the contracting party, and he does not provide the service exclusively to appropriately supervised financial intermediaries. In addition to these elements, the general requirements of the general clause pursuant to Art. 2 para. 3 AMLA (professional activity and activity in the financial sector) must also be met for the AMLA to apply.

99 Virtual currencies are tokens that are actually or, according to the intention of the organizer or issuer, used as a means of payment for the purchase of goods or services or serve to transfer money and value (Art. 4 para. 1bis lit. c AMLA), i.e. payment tokens as defined by FINMA's categorization. The category of payment tokens usually includes stablecoins with a payment function and the cryptocurrencies Bitcoin and Ether. The risk-specific feature of cryptocurrencies compared to other assets lies in the combination of pseudonymity, speed, and mobility.

100 According to FINMA's previous practice, assistance with transfer within the meaning of the general clause of Art. 2 para. 3 AMLA is characterized by (1) a power of attorney, whereby even a collective signature is considered sufficient co-determination, and (2) a change in ownership or creditor status. Financial intermediary activity therefore consists of supporting actions that normally result in the transfer of ownership of third-party assets or a change of creditor. However, since transfers in the blockchain sector take place between pseudonymous wallet addresses, it is often not possible to clearly determine the ownership structure. In this context, the term “assistance” should therefore be interpreted to mean that the financial intermediary provides support for the successful transfer of virtual currencies from one blockchain address to another, which makes the transfer much easier.

101 Assistance with the transfer of virtual currencies can generally be considered in the context of all applications that facilitate the transfer of payment tokens to a third party via a blockchain (e.g., by means of a smart contract). Examples of this are crowdfunding platforms and payment service providers that accept and forward virtual currencies. Access providers that provide an interface for accessing third-party applications in Switzerland or abroad can also provide such assistance with transfers. However, simply providing an IT infrastructure for data transmission without making a significant contribution to the actual transfer of assets is often not sufficient to fulfill the criteria.

102 Assistance with the transfer of virtual currencies that is subject to supervision requires alternatively either power of disposal over the virtual currencies or the existence of a permanent business relationship (without power of disposal). The ongoing business relationship was included as a criterion for subordination (despite criticism from academia) because it is difficult in practice to clarify whether there is legally relevant power of disposal within the framework of a technical solution. This is intended to enable legally secure, risk-based, and practicable subordination decisions without the need for a time-consuming examination of technical circumstances. Particularly where there is a long-term customer relationship and the availability of the service is necessary for the use of the technical solution, the line into financial intermediation is crossed, even though the service provider may not have sole power of disposal.

103 The power of disposal over virtual currencies can be exercised either directly by means of private keys to sign transactions or indirectly by means of control of administered smart contracts or other software applications (e.g., in off-chain payment applications that trigger a transfer in virtual currencies) to confirm, release, and/or block orders. Direct power of disposal is exercised, for example, by custodial wallet providers, who have a private key via multi-signature, which is required to sign the transaction before it can be successfully executed. This also includes operators of central trading platforms who hold customer funds in their own accounts or wallets and act as intermediaries between customers in a trilateral relationship. Indirect power of disposal can be exercised in the context of the administration of a smart contract by means of a single or multi-signature or by the members of a DAO (Decentralized Autonomous Organization) exercising control of the so-called admin key by majority vote.

104 A long-term business relationship must exist between the financial intermediary and its contracting party on whose behalf the financial intermediary transfers the virtual currencies to a third party. The lack of a definition of a long-term business relationship has led to different interpretations in academic circles. The prevailing opinion requires a certain degree of intervention and control over transactions in order to fulfill this criterion. FINMA interprets the term broadly and applies the criterion in particular in the context of decentralized finance as a criterion for subordination. While a business relationship can already result from an implied service, brokerage, or software usage agreement, the permanence of this business relationship usually lies in the continuous nature of the transfer assistance as a contractual service provided by the financial intermediary, which goes beyond one-time interactions. In this context, even the technical connection of a wallet to a smart contract for the purpose of concluding transactions can establish a business relationship. The peculiarities of blockchain technology have prompted FINMA to develop attribution criteria with regard to a permanent business relationship. Such criteria include, in particular, the maintenance of an interface as the front end of a blockchain application, the generation of fees or control and influence over assets, access (e.g., by means of a whitelisting process) or other aspects of the protocol (e.g., by controlling the majority of governance tokens as part of a DAO's governance process).

105 Durability may refer to the behavior of the contracting party and be reflected in continuous use through the creation and management of a wallet or account, repeated transaction orders, or ongoing return generation. With regard to the services of the financial intermediary, the permanence of the business relationship may lie, for example, in the regular collection of fees or the performance of regular updates (bug fixes and product enhancements), configurations (parameter adjustments), or other additional services. However, one-time transactions do not generally constitute a permanent business relationship.

106 Assistance with the transfer of virtual currencies may, for example, take the form of non-custodial staking. In this case, the customer always remains in possession of the private keys that enable them to control the locked assets. The provider generally has only limited power of disposal over the customer's assets, but helps the customer to generate staking rewards by delegating staking rights to the provider (as an indirect instruction) within the framework of operating a validator node on behalf of the customer as a delegator, which constitutes a permanent business relationship.

107 Providers who merely provide software and the necessary licensing, but not such additional services for triggering or executing payments, should not be subject to the AMLA. On the other hand, services for the secure storage of private keys are covered within the scope of non-custodial wallets, even if the latter (e.g., in the context of smart cards) are encrypted and must generally be decrypted by the customer. The risks involved are fundamentally comparable to those of money transmitters. Actual non-custodial wallet providers are therefore subject to the AMLA if, in addition to providing and licensing the software, they also provide additional services (e.g., updates or the connection of third-party service providers for the execution of exchange transactions).

108 In contrast, completely autonomous systems without a permanent business relationship are excluded from the obligation to comply with the AMLA. Decentralized trading platforms that merely bring buyers and sellers together and process transactions without smart contracts with access to the trading platform are not generally subject to the AMLA. This is purely an intermediary activity without involvement in the transfer of virtual currencies. However, practice shows that such systems are rarely completely autonomous. Instead, such applications often have aspects that make it necessary to attribute them to the developers or operators.

109 An exception to the obligation to comply applies if the financial intermediary provides transfer assistance exclusively to financial intermediaries that are subject to appropriate supervision (in Switzerland or abroad) (Art. 4 para. 1 lit. b AMLO). A financial intermediary subject to the AMLA is generally considered to be adequately supervised. In the case of foreign financial intermediaries, the decisive factor is whether a level of protection comparable to that provided by the AMLA exists abroad.

4. Means of payment and payment systems

110 According to Art. 4 para. 1 lit. c AMLO, a payment service is provided if the financial intermediary issues or manages means of payment that are not cash and uses them to make payments to third parties on behalf of its contracting party. This refers to the issuance of means of payment and the operation of a payment system.

111 Art. 4 para. 1bis AMLO specifies means of payment, without limitation, as credit cards (lit. a), traveler's checks (lit. b) and (since 2021) virtual currencies that are used as a means of payment for the purchase of goods or services or serve to transfer money and value (lit. c), i.e., payment tokens.

112 According to the FINMA circular, the issuance of payment instruments and the operation of payment systems are subject to the AMLA beyond the examples mentioned above whenever a three-party relationship exists. The activity is not subject to the AMLA if the issuing entity is also the user of the means of payment within the framework of a two-party relationship, i.e., if it is also the seller of the goods for which the means of payment is used. Vouchers are also not subject to the AMLA as means of payment if they can only be redeemed with the issuing entity. However, it should be noted that if redemption is possible at other group companies, there is no longer a two-party relationship.

113 For the question of subordination, it is irrelevant whether the use of payment instruments or systems is restricted to a specific group of users (closed loop vs. open loop system). A professional issuer of payment instruments or operator of payment systems is always a regulated financial intermediary, provided that the business model is not only conducted between two parties.

114 The value of the payment instrument must be fixed at the time of issue. This also includes, for example, non-rechargeable e-money data carriers. Other examples include debit cards, prepaid cards, mobile payments, and payment tokens. Book money/giro money also falls under this category, but is usually “created” by prudentially supervised institutions, which means that this provision hardly ever applies.

115 Since the money laundering risk associated with the use of credit cards lies with the cardholder, in situations involving four or more parties (credit card organization, acquirer, issuer, processing company), the party that provides the cardholder with access to the payment system and thus has direct customer contact is subject to the AMLA. If credit cards are issued by national issuers, they are subject to the AMLA.

116 For issuers of payment instruments, certain thresholds pursuant to Art. 11 and Art. 12 GwV-FINMA apply, which result in a reduction in the AMLA due diligence obligations.

117 The operation of a payment system is also only subject to the AMLA if it is operated by an organization that is not identical with the users of the payment system. This includes systems that either allow access to a credit balance available on the basis of data storage (reloadable e-money data carriers, debit cards) or allow the storage of a debt that is subsequently invoiced by the payment system operator (credit cards, store cards in three-party relationships, etc.). Prepaid cards that can be used for payment not only with the issuer but also with third parties (e.g., Paysafecard or Aplauz) can be used in a three-party relationship and therefore qualify as a means of payment within the meaning of the AMLA. Since the money laundering risk is located on the end customer side, in addition to the issuer of the means of payment, the party that provides the end customer (purchaser of goods, initiator of the payment transaction) with access to the payment system and thus has direct customer contact (known as the “distributor”) is also subject to the AMLA. The sale of AMLA payment instruments by distributors can take place either in their own name and on their own account (sales model) or as a direct representative of the issuer or another financial intermediary (brokerage model). In principle, both the sales model and the intermediary model are subject to the AMLA, because both models involve direct customer contact and provide end customers with access to the payment system. In the case of the intermediary model, it should be noted that if the legal requirements for the auxiliary person exemption pursuant to Art. 2 para. 2 lit. b AMLO are met, the distributor may be exempted from independent supervision. Operating a payment system necessarily means that the service provider obtains power of disposal over the assets of its customers who use the payment system to transfer their assets to third parties. Services such as PayPal, Click&Buy, Twint, and Tapit are considered payment systems.

118 Payment systems within the meaning of Art. 81 FinMIA, such as SIC (SIX Interbank Clearing) require a FINMA license in accordance with Art. 2 para. 2 lit. dter AMLA in conjunction with Art. 4 para. 2 FinMIA if the functioning of the financial market or the protection of financial market participants so requires and it is not already operated by a bank subject to licensing. While Art. 2 para. 3 lit. b AMLA links qualification as a financial intermediary to payment services, Art. 2 para. 2 lit. d ter AMLA classifies payment systems requiring a license as financial intermediaries under special legislation.

119 According to FINMA's categorization, payment tokens are considered virtual currencies. The category “payment tokens” (synonymous with “cryptocurrencies”) includes tokens that are actually or, according to the issuer's intention, accepted as a means of payment for the purchase of goods or services or serve to transfer money and value (Art. 4 para. 1bis lit. c AMLO). Qualification as a payment token may therefore also result from the fact that a means of payment purpose is only intended in the future or that tokens serve as discount points on a platform for the purchase of third-party goods. Even if a token is linked to gold, it may still qualify as a payment token if it has a corresponding denomination and potential use as a means of payment. An ICO of payment tokens constitutes an issue of means of payment subject to supervision as soon as they can be technically transferred on a blockchain infrastructure. This may already be the case at the time of the ICO or later.

120 If only products or services of the token issuer, but not of third parties, can be paid for with the issued tokens, this constitutes a normal two-party relationship and the token issuer does not qualify as a financial intermediary within the meaning of Art. 2 para. 3 lit. b AMLA. When issuing payment tokens, the purpose of the means of payment must also be the main function of the token and must not merely be an ancillary service to the usage function or main contractual service (see Art. 2 para. 2 lit. a no. 3 AMLO).

121 If a token is used exclusively for the payment of blockchain-related transaction fees by users to validators, this does not constitute a relevant payment function, provided that the mechanism is technically necessary for the operation of the blockchain. In this case, the payment function is merely ancillary to the usage function within the blockchain infrastructure and does not result in the issuance of a payment instrument subject to regulation (provided that the token cannot also be used to pay fees for other functions or services of the blockchain, such as data storage or computing services).

122 The issuance of payment tokens by a smart contract that has been programmed and activated by a person is, despite the algorithmic issuance of the tokens, attributable to the area of responsibility of the person who activated the contract in terms of an overall assessment as an issuance of means of payment subject to the AMLA.

123 In the case of an airdrop, despite the free issuance, professional activity may be deemed to have been carried out in this context, in particular if the issuer of a payment token enters into business relationships with more than 20 contracting parties per calendar year in accordance with Art. 7 para. 1 AMLO (lit. b) that are not limited to the one-time activity of issuance, or if the airdrop exceeds a total volume of CHF 2 million (token price x number of tokens issued) per calendar year (lit. d).

124 If stablecoins are issued as a means of payment on an open-access transaction system such as the Ethereum blockchain, particular attention must be paid to the increased risks relating to money laundering, terrorist financing, and sanctions evasion. Due to the openness of the system, once the stablecoin has been issued, the issuer only has the option of exercising control when the underlying value is redeemed. If no appropriate technical measures are taken, the due diligence obligations under money laundering law can only be fulfilled in relation to the first and last persons who have access to the stablecoin. Persons who buy or sell the stablecoin on the open platform in between are beyond the control of the issuing institution. According to FINMA Supervisory Notice 06/2024, all persons holding stablecoins must be adequately identified by the issuing institution or by appropriately supervised financial intermediaries. In order to address the risks and meet money laundering requirements, contractual and/or technological transfer restrictions are necessary when stablecoins are issued by supervised institutions. The technical implementation of the requirements is left to the stablecoin issuers. However, the requirements can be implemented, for example, by means of a whitelisting process or transfer restrictions programmed into the smart contract.